| Basics |

|

Who am I?

E-Mail Me |

| Links |

|

My Other Blog

The Socialism of Fools johnpaulpagano Blogroll Kerry Howley Luke Ford Michael Totten Norman Geras (RIP) Terry Glavin Undercover Black Man (RIP) Great Writers Christopher Hitchens (RIP) Oliver Kamm (Sadly, pay) Columnists Anne Applebaum Jeffrey Goldberg Journals & Commentary The Atlantic Butterflies and Wheels Dissent Magazine Fathom Journal Moment Magazne Tablet Magazine The New Yorker The Tower Magazine |

|

|

Monday, April 26, 2004

This Christian Love

A Review of The Passion of the Christ

It's way overdue, but I just saw Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. I will comment on it at length, but let me start by saying, in reference to the controversy attending the film, I was predisposed disfavorably to making rash conclusions about it. First, I have always liked Mel Gibson. More important, I am aware that elements of the Gospels, considered today, are simply anti-Semitic, and there's not a lot an interpreter of the Passion can do about that if he intends to be true to the story. Also, I knew that many Christians were greatly moved by the movie, and had respect for that. To be honest, on some level it moved me. But The Passion is a violative nightmare of a film, and it convinced me of this long before it was over.

Let's get the good stuff out of the way: the movie is beautifully shot, viscerally moving (to say the least), and I think the choice to script it in Aramaic, Hebrew and "street Latin" was brilliant. This latter element lends the movie a profundity it could not have had otherwise. Have you ever heard an opera sung in English? When I do, it sounds cringingly awkward and silly to me; whereas hearing an opera in Latin or Italian or French sounds mysterious and beautiful, the voice really becoming an instrument in its own right in the absence of understanding. Scripting The Passion in ancient languages does the same. As one reviewer observed, it allows the film to avoid the dated feel of other Passion movies that are written and performed in stage English by graying actors. It effectively removes us from that contrived theatrical milieu.

Now, the bad stuff. There are a number of areas in which the movie is deeply disturbing. To begin, I will use Leon Wieseltier's laconic summation, from his wonderfully written review in The New Republic:

I don't agree that this is the only cinematic achievement of the movie, but Wieseltier's claim about its precedential violence is true. For the first time in my life, I was actually made to feel nauseous by a work of art, and I am not a squeamish person -- I have forensic wound atlases in my library. I was also exhausted by the end of the film. There is scant scriptural reason for exaggerating the violence of Jesus' torture to this extent. People argue that Gibson wanted to realistically portray the enormity of the debt Jesus was shouldering on our behalf. Fine, but none of the Gospels nor any of their interpreters throughout two millenia saw fit to dumb it down like this. Plus, no human could survive 25% of what Jesus endures in The Passion.

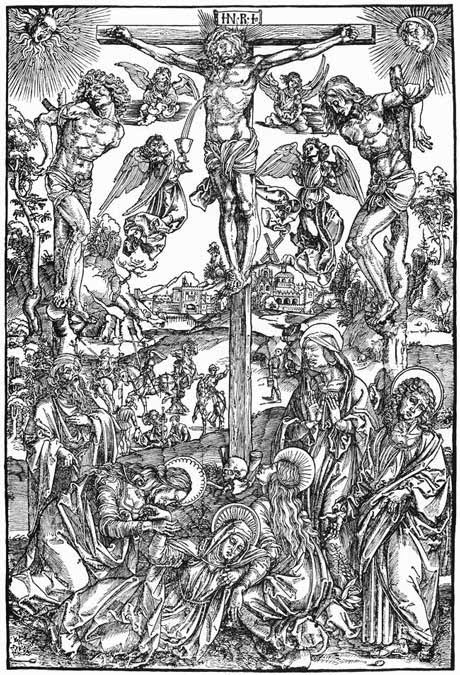

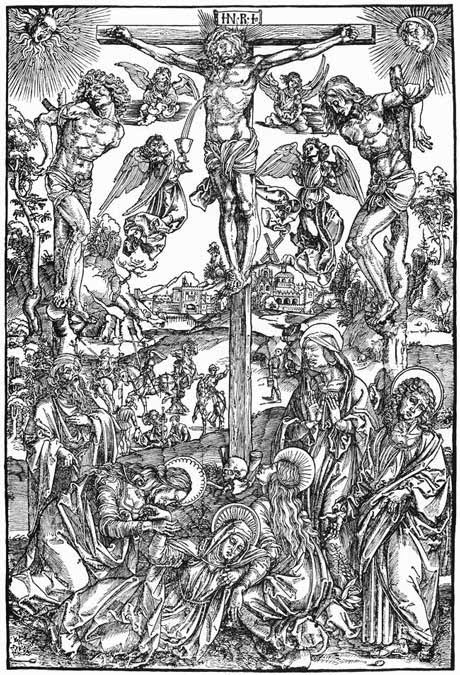

Some people say that medieval depictions of the Passion and the martydom of saints can be grisly, and that is true, but the comparison cannot be sustained in terms of the intensity of the individual examples or the media themselves. I have been to Rome and seen some scary, wall-sized paintings of Biblical slaughters -- The Massacre of the Innocents comes to mind. The medium of paint just doesn't approach that of film, and Grunewald amounts to a workplace-safe Get Well card by comparison with The Passion.

Wieseltier argues:

He's right. This is Christian love Taliban-style, a Grand Guignol of such mind-numbing luridness that it would sicken those in the highest seats of the stadium. That so many Christians have cited the ability of this movie to inspire love in them is utterly confusing and frightening.

I believe the movie is anti-Semitic. As I said before, there is a certain amount of anti-Semitism baked into the story of Jesus' betrayal, scourging and crucifixion. It's unavoidable, as the Jewish establishment was not kind to the inchoate Christian movement, and I think the impression rendered by many depictions of the Passion that "the Romans are brutish, but the Jews are evil" is justified by the original texts. This doesn't invalidate the narrative foundation of Christianity for me, even as a Jew, because it's anachronistic to consider it in terms of modern or even medieval anti-Semitism, and anyway, it's really not the point of Christ's travails. The writers of the Gospels, while conscious of Jewish rejection and persecution, did not intend to compose revanchist propaganda. That we are all responsible for the necessity of Christ's sacrifice is the message they were trying to convey.

Gibson, however, moves resolutely beyond this into an imagistic and narrative realm in which Jews are portrayed in a classically anti-Semitic way. Early in the movie, a covey of Rabbis, led by Caiaphas, the Temple high priest who architects Jesus' torturous death, meets with Judas. A dour Caiaphas casts a filthy bag of coins at him, and it bursts open in his fumbling hands in slow-motion. Judas is gripped by crapulent lust for the silver and nervous apprehension of his treachery. The message is unmistakeable and unreconstructed.

The rabbis, as Wieseltier puts it, are otherwise "gold and cold":

Yes, but even more dangerously:

Gibson's most anti-Semitic statement is his insistence that the Romans are either loutish gorillas or conflicted over the persecution of Jesus, but that the Jews outside his coterie keen en bloc for his blood. They gladly pull the lever on him. (The insertion of sympathetic Simon later into the narrative doesn't mitigate the contrast.) Yes, again, to a degree this is justified by the original texts. But as many reviewers noted, the Gospels are not reliable historical documents, and consequently, interpretations of them vary greatly. Examining those variations reveals much about the maker and his audience. Charles Krauthammer writes:

And as I said, the Gospels are not revanchist propaganda. Gibson embellishes them, even adds to them, and proudly turns them into that. A decidedly modern rendering of the figure of Satan trolls through the film, and is used to harrowing effect. One of the ways in which she is deployed is as a foil for Pilate's wife, Claudia. Aware of the scourging of Jesus and watching his show-trial by Pilate and the Jewish mob, Claudia is reduced to tears through phases of burgeoning piety. She comforts Mary and Mary Magdalene, giving them towels; all three are ensconced in maternal love. By contrast, Satan, who is depicted as an androgynous woman with a man's voice, lurks among the braying Jews as the skin is literally flogged off Jesus, watching, carrying an albino baby with an old, dwarven face and hair on its back.

This brings up another nasty facet of the movie: its homophobia. It has been noted less, but this hatred is only marginally less present in the film. Herod is portrayed as a preening queen, interrupted from a Sodomite orgy to pass judgment on Christ. (I can find no historical justification for this.) He simpers and sends Jesus back to Pilate. Satan, the locus of evil, is a dual-gendered freak who births snakes and demonic, progeriac children. Matt Zoller Seitz writes in the New York Press:

To be fair, I don't think Gibson emphasizes the theme of repressed lust for Mary Magdalene, or really treats it at all. Seitz seems to mention it only because Monica Bellucci is really hot. But he's right about the use of gender in the film. There is a scene during the procession through the Stations of the Cross in which Jesus, having been clobbered to the ground, is shot at an upwards angle rising with the impossibly heavy cross on his shoulder like, well, Sylvester Stallone. It is gratuitous and cheesy, and revelatory of Gibson's (and unfortunately, our) sensibility. Gibson is clearly not a stupid man, but his aesthetic often is. It is literalistic, folkish, and above all juvenile. His movie is a breviary of lowest-common-denominator appeals: ultra-violence, sinister Jews, fags, dykes -- even albinos and dwarves!

But, hey, it also works. I liked Braveheart and again, on some level I admit I liked this too. The movie soils you on both visceral and cerebral planes, but somehow becomes tolerable without actually relenting in its assault on the viewer. And mostly, you have to think about what is hateful about it. In the absence of that sort of reflection, I can see why the average Christian would be knocked on his ass by this movie. There is a captivating moment, upon Jesus' death, when a rain drop symbolizing the tear of God envelops the scene at Calvary. It provides a brief, quiet and sublime respite. But then it crashes to earth, and, wait for it... hysterical rabbis watch the Temple split down the middle.

There are other times when Gibson spells things out for you. Besides leaving the Aramaic utterance of the original "blood libel" in the script, whose subtitle will surely reappear in foreign and DVD releases, consider this dialogue, a narrative centerpiece of the film:

That couldn't be more clear in Gibson's fundamentalist rendering. After witnessing the most relentless violence ever filmed, and a photorealistic crucifixion, we see Jesus on the cross, dolorous, excruciated. Caiaphas ambles over, gloating, to taunt Jesus. Jesus tells Caiaphas that he prays for him. When asked whether he is anti-Semitic, Gibson responds: "I don't want to lynch any Jews... I love them, I pray for them." Sure, it's horrifying that Jews would be targeted in or outside of this movie. But that anyone might be targeted by this Christian love, which drove the maker of this savage, unremitting holocaust of a film, and which "exalted" so many of the Christians exposed to it, is something worth considering at length.

This Christian Love

A Review of The Passion of the Christ

It's way overdue, but I just saw Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. I will comment on it at length, but let me start by saying, in reference to the controversy attending the film, I was predisposed disfavorably to making rash conclusions about it. First, I have always liked Mel Gibson. More important, I am aware that elements of the Gospels, considered today, are simply anti-Semitic, and there's not a lot an interpreter of the Passion can do about that if he intends to be true to the story. Also, I knew that many Christians were greatly moved by the movie, and had respect for that. To be honest, on some level it moved me. But The Passion is a violative nightmare of a film, and it convinced me of this long before it was over.

Let's get the good stuff out of the way: the movie is beautifully shot, viscerally moving (to say the least), and I think the choice to script it in Aramaic, Hebrew and "street Latin" was brilliant. This latter element lends the movie a profundity it could not have had otherwise. Have you ever heard an opera sung in English? When I do, it sounds cringingly awkward and silly to me; whereas hearing an opera in Latin or Italian or French sounds mysterious and beautiful, the voice really becoming an instrument in its own right in the absence of understanding. Scripting The Passion in ancient languages does the same. As one reviewer observed, it allows the film to avoid the dated feel of other Passion movies that are written and performed in stage English by graying actors. It effectively removes us from that contrived theatrical milieu.

Now, the bad stuff. There are a number of areas in which the movie is deeply disturbing. To begin, I will use Leon Wieseltier's laconic summation, from his wonderfully written review in The New Republic:

"The only cinematic achievement of The Passion of the Christ is that it breaks new ground in the verisimilitude of filmed violence."

I don't agree that this is the only cinematic achievement of the movie, but Wieseltier's claim about its precedential violence is true. For the first time in my life, I was actually made to feel nauseous by a work of art, and I am not a squeamish person -- I have forensic wound atlases in my library. I was also exhausted by the end of the film. There is scant scriptural reason for exaggerating the violence of Jesus' torture to this extent. People argue that Gibson wanted to realistically portray the enormity of the debt Jesus was shouldering on our behalf. Fine, but none of the Gospels nor any of their interpreters throughout two millenia saw fit to dumb it down like this. Plus, no human could survive 25% of what Jesus endures in The Passion.

Some people say that medieval depictions of the Passion and the martydom of saints can be grisly, and that is true, but the comparison cannot be sustained in terms of the intensity of the individual examples or the media themselves. I have been to Rome and seen some scary, wall-sized paintings of Biblical slaughters -- The Massacre of the Innocents comes to mind. The medium of paint just doesn't approach that of film, and Grunewald amounts to a workplace-safe Get Well card by comparison with The Passion.

Wieseltier argues:

"The Passion of The Christ is an unwitting incitement to secularism, because it leaves you desperate to escape its standpoint, to find another way of regarding the horror that you have just observed."

He's right. This is Christian love Taliban-style, a Grand Guignol of such mind-numbing luridness that it would sicken those in the highest seats of the stadium. That so many Christians have cited the ability of this movie to inspire love in them is utterly confusing and frightening.

I believe the movie is anti-Semitic. As I said before, there is a certain amount of anti-Semitism baked into the story of Jesus' betrayal, scourging and crucifixion. It's unavoidable, as the Jewish establishment was not kind to the inchoate Christian movement, and I think the impression rendered by many depictions of the Passion that "the Romans are brutish, but the Jews are evil" is justified by the original texts. This doesn't invalidate the narrative foundation of Christianity for me, even as a Jew, because it's anachronistic to consider it in terms of modern or even medieval anti-Semitism, and anyway, it's really not the point of Christ's travails. The writers of the Gospels, while conscious of Jewish rejection and persecution, did not intend to compose revanchist propaganda. That we are all responsible for the necessity of Christ's sacrifice is the message they were trying to convey.

Gibson, however, moves resolutely beyond this into an imagistic and narrative realm in which Jews are portrayed in a classically anti-Semitic way. Early in the movie, a covey of Rabbis, led by Caiaphas, the Temple high priest who architects Jesus' torturous death, meets with Judas. A dour Caiaphas casts a filthy bag of coins at him, and it bursts open in his fumbling hands in slow-motion. Judas is gripped by crapulent lust for the silver and nervous apprehension of his treachery. The message is unmistakeable and unreconstructed.

The rabbis, as Wieseltier puts it, are otherwise "gold and cold":

"The figure of Caiaphas, played with disgusting relish by an actor named Mattia Sbragia, is straight out of Oberammergau. Like his fellow priests, he has a graying rabbinical beard and speaks with a gravelly sneer and moves cunningly beneath a tallit-like shawl streaked with threads the color of money. He is gold and cold. All he does is demand an execution."

Yes, but even more dangerously:

"[Caiaphas] and his sinister colleagues manipulate the ethically delicate Pilate into acquiescing to the crucifixion. (You would think that Rome was a colony of Judea.) Meanwhile the Jewish mob is regularly braying for blood. It is the Romans who torture Jesus, but it is the Jews who conspire to make them do so."

Gibson's most anti-Semitic statement is his insistence that the Romans are either loutish gorillas or conflicted over the persecution of Jesus, but that the Jews outside his coterie keen en bloc for his blood. They gladly pull the lever on him. (The insertion of sympathetic Simon later into the narrative doesn't mitigate the contrast.) Yes, again, to a degree this is justified by the original texts. But as many reviewers noted, the Gospels are not reliable historical documents, and consequently, interpretations of them vary greatly. Examining those variations reveals much about the maker and his audience. Charles Krauthammer writes:

"... Gibson's personal interpretation is spectacularly vicious. Three of the Gospels have but a one-line reference to Jesus's scourging. The fourth has no reference at all. In Gibson's movie this becomes 10 minutes of the most unremitting sadism in the history of film. Why 10? Why not five? Why not two? Why not zero, as in Luke? Gibson chose 10."

And as I said, the Gospels are not revanchist propaganda. Gibson embellishes them, even adds to them, and proudly turns them into that. A decidedly modern rendering of the figure of Satan trolls through the film, and is used to harrowing effect. One of the ways in which she is deployed is as a foil for Pilate's wife, Claudia. Aware of the scourging of Jesus and watching his show-trial by Pilate and the Jewish mob, Claudia is reduced to tears through phases of burgeoning piety. She comforts Mary and Mary Magdalene, giving them towels; all three are ensconced in maternal love. By contrast, Satan, who is depicted as an androgynous woman with a man's voice, lurks among the braying Jews as the skin is literally flogged off Jesus, watching, carrying an albino baby with an old, dwarven face and hair on its back.

This brings up another nasty facet of the movie: its homophobia. It has been noted less, but this hatred is only marginally less present in the film. Herod is portrayed as a preening queen, interrupted from a Sodomite orgy to pass judgment on Christ. (I can find no historical justification for this.) He simpers and sends Jesus back to Pilate. Satan, the locus of evil, is a dual-gendered freak who births snakes and demonic, progeriac children. Matt Zoller Seitz writes in the New York Press:

"For no apparent reason, the film depicts King Herod as a bewigged, Dom DeLuise-style fop lording over a court full of decadent queens. Gibson also casts the role of Satan with an actress, shaves her eyebrows, masks her in albino-white face paint, dresses her in a black hooded gown and hires a man to dub her voice. The implied opposition could not be more obvious: Goodness is exemplified by Jesus -- a macho man who chose not to kick ass; a stud who chose not to have sex with Mary Magdalene -- while evil is represented by a creature of indeterminate gender."

To be fair, I don't think Gibson emphasizes the theme of repressed lust for Mary Magdalene, or really treats it at all. Seitz seems to mention it only because Monica Bellucci is really hot. But he's right about the use of gender in the film. There is a scene during the procession through the Stations of the Cross in which Jesus, having been clobbered to the ground, is shot at an upwards angle rising with the impossibly heavy cross on his shoulder like, well, Sylvester Stallone. It is gratuitous and cheesy, and revelatory of Gibson's (and unfortunately, our) sensibility. Gibson is clearly not a stupid man, but his aesthetic often is. It is literalistic, folkish, and above all juvenile. His movie is a breviary of lowest-common-denominator appeals: ultra-violence, sinister Jews, fags, dykes -- even albinos and dwarves!

But, hey, it also works. I liked Braveheart and again, on some level I admit I liked this too. The movie soils you on both visceral and cerebral planes, but somehow becomes tolerable without actually relenting in its assault on the viewer. And mostly, you have to think about what is hateful about it. In the absence of that sort of reflection, I can see why the average Christian would be knocked on his ass by this movie. There is a captivating moment, upon Jesus' death, when a rain drop symbolizing the tear of God envelops the scene at Calvary. It provides a brief, quiet and sublime respite. But then it crashes to earth, and, wait for it... hysterical rabbis watch the Temple split down the middle.

There are other times when Gibson spells things out for you. Besides leaving the Aramaic utterance of the original "blood libel" in the script, whose subtitle will surely reappear in foreign and DVD releases, consider this dialogue, a narrative centerpiece of the film:

Pilate: Do you not know that I have power to crucify you, and power to release you?

Jesus: You could have no power at all against me unless it had been given you from above. Therefore the one who delivered me to you has the greater sin.

Jesus: You could have no power at all against me unless it had been given you from above. Therefore the one who delivered me to you has the greater sin.

That couldn't be more clear in Gibson's fundamentalist rendering. After witnessing the most relentless violence ever filmed, and a photorealistic crucifixion, we see Jesus on the cross, dolorous, excruciated. Caiaphas ambles over, gloating, to taunt Jesus. Jesus tells Caiaphas that he prays for him. When asked whether he is anti-Semitic, Gibson responds: "I don't want to lynch any Jews... I love them, I pray for them." Sure, it's horrifying that Jews would be targeted in or outside of this movie. But that anyone might be targeted by this Christian love, which drove the maker of this savage, unremitting holocaust of a film, and which "exalted" so many of the Christians exposed to it, is something worth considering at length.

|